Forensic investigative genealogy (FGG), also called investigative genetic genealogy (IGG), burst into the public perception in April 2018 with the arrest of the Golden State Killer, a serial killer, rapist, and former police officer who was active in the 1970s and ’80s. He remained at large until Barbara Rae-Venter and a team of FBI agents used DNA techniques developed by genealogists to identify him.

Although the Golden State Killer wasn’t the first case solved with FGG techniques, it got the most media attention. Both law enforcement and genetic genealogy changed overnight.

Since then, IGG has been akin to the Wild West. Anyone can hang up a shingle and market themselves to law enforcement as an IGG professional. There is no oversight, no credentialing, no education requirement, no minimum qualification, no set of ethical standards.

Since then, IGG has been akin to the Wild West. Anyone can hang up a shingle and market themselves to law enforcement as an IGG professional. There is no oversight, no credentialing, no education requirement, no minimum qualification, no set of ethical standards.

And it shows. The field is marred by both public reports of unethical behavior and private gossip networks describing infractions.

That may change soon.

A new paper in Forensic Science International announces the formation of a new Board for Certification of Investigative Genetic Genealogy (BCIGG). The paper was co-authored by David Gurney, a law professor; Margaret Press, co-founder of the DNA Doe Project; CeCe Moore and Carol I. Rolnick, employees of Parabon NanoLabs; and Andrew Hochreiter and Bonnie L. Bossert, both genetic genealogists. Their website will be here.

IGG Needs to Be Regulated

The BCIGG argues, first, that investigative genetic genealogy desperately needs oversight and, second, that the oversight should come from within the field itself. I agree wholeheartedly with the first point. The second should be debated thoughtfully by the genealogy and forensics communities.

The authors list four reasons that some kind of credentialing is necessary: (1) the privacy of innocent people who are drawn unawares into criminal investigations, (2) public trust in IGG itself, (3) proficiency and ethical behavior of investigative genetic genealogists, and (4) accountability for incompetent or unethical practitioners. These are all excellent reasons why IGG needs an independent body to oversee standards and certification of practitioners.

The authors list four reasons that some kind of credentialing is necessary: (1) the privacy of innocent people who are drawn unawares into criminal investigations, (2) public trust in IGG itself, (3) proficiency and ethical behavior of investigative genetic genealogists, and (4) accountability for incompetent or unethical practitioners. These are all excellent reasons why IGG needs an independent body to oversee standards and certification of practitioners.

The paper also argues that oversight should come from within IGG rather than from the government. One reason is that IGG often spans jurisdictions, with most practitioners working remotely with law-enforcement agencies in other states or countries. Requiring a separate license or certification in each jurisdiction would be burdensome for everyone involved, agencies and practitioners alike.

Another reason that IGG should be self-governing, according the authors, is that the field is advancing too rapidly for individual state boards to keep abreast of the latest developments. As someone committed to bringing new tools to the community, I applaud this logic.

Instead, the authors write, “The best way to meet these conflicting realities is to allow for the IGG community to regulate itself and for states to pass laws requiring any IGG practitioner who works in their jurisdiction to be certified by a private board of IGG experts.”

Whether FGG/IGG should regulate itself or be brought under the auspices of an existing field is an open question. But if not IGG itself, then who?

Why Not BCG?

First, some of the BCG standards are not compatible with ethical IGG. For example, Standard 51 states that “genealogists select DNA tests, testing companies, and analytical tools for their potential to address the genealogical research question.” However, the largest DNA databases–with the best potential to address most genealogical questions–do not allow IGG at all. Thus, any ethical IGG practitioner would fail this standard.

Similarly, Standard 57 holds that “genealogists share living test-takers’ data only with written consent to share that data.” By definition, IGG practitioners are working with the DNA of someone unknown who has not consented … and likely wouldn’t given a choice. This standard might permit IGG for unidentified remains, but it would not permit the investigation of living suspects.

Second, the BCG certification process is too onerous to be mandatory for IGG work. BCG applicants tell me they spent up to 1,000 hours on their portfolios, equivalent to a full-time job for six months. That’s typically after they’ve spent years becoming proficient genealogists and thousands of dollars on institutes, journals, society memberships, books, and subscriptions. There’s a 60% fail rate.

It would likely cost a police department more than $100,000 to certify an in-house detective under the current BCG program. That includes the salary of the detective applying and the salary of a replacement officer to do police work while the portfolio is being assembled. That figure assumes the detective passes the first time.

Finally, only one of the four components in a BCG portfolio is directly relevant to IGG: the research report. IGG practitioners don’t transcribe and abstract documents. They don’t need to resolve conflicting evidence; the suspect’s CODIS markers either do or do not match the crime-scene evidence. And they don’t need to document three generations of a family to the Genealogical Proof Standard.

If a BCG Certified Genealogist is the PhD of genealogy, an IGG practitioner is more of tradesperson. They need a guild to maintain standards, but they don’t need a CG.

Why Not Forensic Sciences?

The argument that the existing regulatory framework for forensic sciences should not apply to IGG is less compelling. The authors contend that they are only providing leads, as opposed to evidence, so they should not be subject to the same criteria. That is faulty logic. A forensic scientist who examines fibers from a crime scene, for example, is only producing a lead. Further evidence will always be required to confirm that those fibers were associated with the suspect.

Also, not all for ensic scientists work with physical evidence. They may specialize in analyzing cybercrimes or financial records, so there’s a precedent for “armchair” investigators, just as DNA sleuths may work primarily online. DNA-based conclusions about relationships are still evidence that leads to a suspect.

ensic scientists work with physical evidence. They may specialize in analyzing cybercrimes or financial records, so there’s a precedent for “armchair” investigators, just as DNA sleuths may work primarily online. DNA-based conclusions about relationships are still evidence that leads to a suspect.

The authors also claim that IGG is different because “There can be no contamination of evidence in IGG.” I question this. Many biological samples are mixed (for example, a rape kit will have DNA from the rapist and the victim, and possibly even from a consensual partner of the victim.) We also know of at least one case in which an IGG laboratory sent the wrong data file to the genealogist, contaminating the investigation until the error was discovered.

I suspect the main objection to forensic science certification is the education requirement. The American Board of Criminalistics, for example, requires a bachelor’s degree in a biological or forensic science for each of their eight examinations. Many well-known IGG practitioners either have a degree in another field or no college degree at all. Then again, ABC certification is not required to work in forensics, and ABC could conceivably waive that requirement for applicants with sufficient real-world experience.

Working within the forensics field would allow FGG/IGG to capitalize on existing knowledge, use established exam-delivery platforms, and collaborate fully with forensic DNA lab technicians, criminal justice experts, defense lawyers and prosecutors.

As an outsider to FGG/IGG, I can’t say what would be best. I do question the need to reinvent a wheel that might only need new spokes, though.

Ethical Concerns About Consent

Unfortunately, the authors of the paper fail to adequately address two major ethical concerns: consent and genetic privacy.

BCIGG emphasize that consent by members of the public to have their DNA exposed to IGG investigations is critically important. They write:

- “IGG relies on … the consent of individuals who have uploaded their DNA profiles to genetic genealogy databases.”

- “IGG requires a critical mass of individuals to consent to having their DNA profiles used for IGG searching.”

- “[We] worry that IGG practitioners are ignoring terms of service and, thus, drawing individuals into IGG searching without their consent.”

With these repeated statements, the authors suggest that they themselves are only accessing the DNA profiles of individuals who have consented to that purpose. This implication is not true. Superficially, though, it appears to be the case.

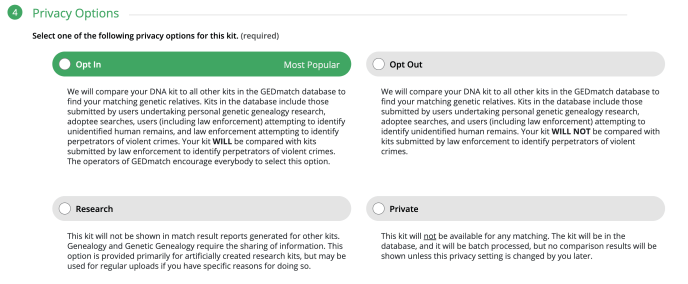

Take GEDmatch, for example, one of the two genealogy databases that sells access to law enforcement. If Joan Q. Public were to add a new DNA profile to GEDmatch today, she would see very clear language about her choices: “Opt In” to all IGG exposure, “Opt Out” of some–but not all–law-enforcement investigations, or be invisible to others in the database (Research or Private status).

The problem lies in the fact that the vast majority of people at GEDmatch, perhaps 90% or more, weren’t given that choice. They were already in the database by the time that wording appeared.

To understand the true nature of “consent” at GEDmatch requires some backstory. In December 2018, the then-owner of GEDmatch gave his personal permission for Parabon to investigate a case that violated the Terms of Service (TOS). In the ensuing outrage, GEDmatch created an opt-in system, such that only people who had given explicit permission would be exposed to IGG cases. So far, so good.

Then, in January 2021, GEDmatch’s new owners changed the TOS to expose all visible kits to law-enforcement cases involving unidentified bodies, regardless of user preferences. “Your opt-in and opt-out settings remain unchanged,” they reassured, while immediately giving IGG practitioners access to ≈1.4 million DNA profiles for some cases without consent. I suspect most users still have no idea that the “Opt Out” setting doesn’t opt them out of all criminal investigations.

GEDmatch did not update the wording on their upload page until around September 2021. (They did not reply when I asked them the exact date.) They have never, to my knowledge, fully explained to their existing users how the change in TOS affected their exposure to IGG cases. In other words, only the people who have uploaded since late 2021–less than 10% of the total database–have been given a real choice.

The situation at FamilyTreeDNA, the other genealogy company that sells access to law enforcement, is arguably even worse. In response to their own TOS violations, they created an opt-out system for IGG matching in March 2019 rather than an opt-in one. Anyone in the US who uploads to the FamilyTreeDNA database is exposed to IGG unless they take extra, hard-to-find, steps to opt out. This is not consent.

Thus, when the authors of the FSI paper write that “IGG practitioners are relegated to a select subset of a limited number of genetic genealogy databases where individuals have given consent to have their DNA profiles compared to Subjects in IGG,” they are being disingenuous. Maybe some individuals at GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA have given consent, but certainly not all of them, or even a majority.

One can only hope these linguistic slips were not intentional.

Ethical Concerns About Genetic Privacy

The BCIGG board fails to acknowledge the elephant in the room: the genetic privacy of the person under investigation. While a suspected murderer or rapist is not a particularly sympathetic character, they do have constitutional rights in the United States. The Fourth Amendment protects against warrantless searches of our persons.

When the Supreme Court decided that suspects can be subjected to CODIS testing, their argument rested in part on the understanding that (1) no sensitive personal information be revealed and (2) that privacy be safeguarded. Neither argument applies here. First, unlike with CODIS testing, there is no biological way to disentangle private genetic information from the SNP tests that are used for genetic genealogy. Second, that sensitive information is being handed over to private citizens and for-profit companies who may simply be the lowest bidder.

In a footnote, the authors write “the IGG practitioner never has access to the raw biological sample.” Again, this is misleading. The biological sample itself (blood, semen, etc.) is not constitutionally protected information; the raw DNA data file is. IGG companies often do have access to that file.

Even without the raw data file, it’s possible to infer private information about someone simply by analyzing segment data. For example, I was able to identify two carriers of cystic fibrosis through triangulation. It took me 5 minutes.

With proper judicial oversight, there’s no reason that violent criminals should walk free. However, we do need to ensure that IGG practitioners understand the Fourth Amendment concerns and that the entire process–from sample extraction to DNA analysis to bioinformatics to genetic genealogy–is regulated. The last phase does not happen in a vacuum.

The Board Members

The membership of the board have a broad range of experience and skill sets. The makeup has changed since the paper was published, according to a board member I communicated with while fact-checking this article.

- David Gurney, JD/PhD, is a law professor who teaches constitutional law, investigative genetic genealogy, and other topics at Ramapo College of New Jersey. He is a DNA “Search Angel” and directs the Investigative Genetic Genealogy Center, which aims to use IGG to exonerate the wrongfully convicted.

- Margaret Press, PhD, is the co-founder and CEO of the non-profit DNA Doe Project. A genealogist from a young age as well as a published mystery writer, she was among the first to recognize the potential of genetic genealogy for forensics. She has extensive experience using DNA, even highly degraded samples, to restore names to unidentified victims.

- Carol Isbister Rolnick is a pioneer of genetic genealogy for unknown parentage searches and an investigative genetic genealogist at Parabon NanoLabs. Her casework experience–nearly 50 IGG solves–positions her as an authority on best practices and ethical considerations for IGG.

- Andrew Hochreiter, MEd, MIS, is an avid genetic genealogist and experienced teacher on DNA tools and techniques. He has credentialing and standards experience from his professional career that will directly benefit BCIGG.

- Bonnie Bossert, MBA, GC, is also an experienced genetic genealogist and educator in the field and an expert in the development of ANSI and ISO standards in the financial industry

- Michele Kennedy, CLEA, has been in law enforcement for nearly 30 years and a crime analyst for the past 25 years. She united her passions for law enforcement and genetic genealogy–she has solved more than 100 adoptee cases–to form her own successful IGG company. She oversaw the Certification Commission for the International Association of Crime Analysts for 10 years and brings that skill set to BCIGG.

- CeCe Moore has resigned from the board because of other obligations.

What’s curious is who’s not on the board. There’s no one from the forensic sciences. No one from the Department of Justice. No prosecutors or defense attorneys. No experts in civil liberties. And some of the most prominent names in IGG are not listed.

All in all, I applaud the effort to provide much needed oversight to IGG. Hopefully, the board will either expand their membership to include more of the key players in forensics or work directly with forensic scientists to create the best possible certification process.

Reference

David Gurney, Margaret Press, CeCe Moore, Carol I. Rolnick, Andrew Hochreiter, Bonnie L. Bossert, 2022, The need for standards and certification for investigative genetic genealogy, and a notice of action, Forensic Science International 341: 111495, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2022.111495. (This link should provide free access until December 4.)

Leah, I applaud your detailed analysis of the IGG issues. I am a retired LEO and former Colorado Homicide Investigators Association member. I researched the issue of accreditation in this field during the year. I found a program offered by the University of New Haven, Connecticut entitled “Forensic Genetic Genealogy.” The curriculum last 12 months. If you are successful, the university will issue you a certificate. However, in speaking with the Program Director, Claire L. Glynn, Ph.D., we mutually agreed that the issuance of a certificate is not the something as being Board Certified by an independent body, as a Forensic Genetic Genealogist or an Investigative Genetic Genealogist, its in addition to your training. That being said, I for one have waited a long time for the benefits that could come from forensic genetic genealogy. I also endorse the much-needed procedures and safeguards advocated by so many in finding a balance that meets the demands of justice.

Thank you for sharing your perspective as a retired LEO. Dr. Glynn was quite helpful to me in understanding the forensics perspective on the issue. To be honest, when I started writing, I was much more enthusiastic about the idea of BCIGG as a stand-alone body. Her thoughts made a certification from within forensic sciences seem more realistic.

I do not think my 1000 hours is representative of the effort it normally takes to build a BCG portfolio. As I said in our exchange, I could have shaved 500 hours off by choosing an easier family for my Kinship Determination Project. The KDP does not have to be a difficult camily. I chose one who lived on four continents and did research in six countries in seven languages. It does not have to be that complicated. Only the case study needs to be complex. Many people choose to create portfolio items they want to use in other ways, and spend more time on it than necessary for certification.

My 1000 hours included education time. I was self-taught when I went on the clock, never even took a genealogy class (by the time I could afford these, I had moved beyond the beginner level that is taught in the Netherlands). When I went on the clock, I had just started a business. I would have spent much time on education even had I not chosen to go for certification. Any good professional, especially in the early stages of a new career, will educate themselves.

I’ve asked the “how many hours did it take” for years, of both BCG applicants and ProGen leaders. The answers are remarkably consistent. Almost everyone gives some version of “Between 500 and 1000 hours. I was closer to 1000 but could have done it faster if …”

This is a good reminder to check all the settings for all database platforms for each genetic DNA kit that we manage, especially those for relatives who have since died. They had no idea of the forensic advances when they authorized us to handle their kits & now we have to do our best to guess their intentions…

What responsibility & liability do we face in such cases??

Good questions about responsibility and liability. We’re largely in uncharted territory.

Leah, I am a big fan of your work-We need your voice in the conversation. There is a need for this type of expertise in the field of criminal investigation. I was involved in 30 homicide and missing person cases over an 11-year period, which does not make me an expert. But-I did learn a few things. Did you know that many Coroner/ME offices around the country are storing more than 16, 000 Unidentified Human Remains (UHR) according to a report released by the DOJ some ten years ago? The victims/deceased are in three categories: 1. Homicide 2. Suicide 3. Accidental Death. The victim/deceased demographic includes men, women, and children. All of these people were found deceased with no identification on their person. I voiced the opinion before retirement that LEO agencies should be given at least enough regulatory authority to access commercial databases in the hope of finding the next of kin. This idea begs the questions-how many types of regulated authorizations do you need? In my opinion–three. One for each category-homicide, suicide, and accidental death. The last two don’t have criminal investigative implications and could reunite a John or Jane Doe to a loved one in a timely manner. The remaining homicide cases would need different procedures and judicial safeguards. I also think that commercial database access could be used to identify unknown soldiers. I’m speaking as someone confronted with the day-to-day reality of unattended death, which is a complicated process. This does not even address other violent crimes for which LEO agencies have sought DNA matches. This issue and crime are not going away.

Thank you for sharing more about your background and experiences.

I tried to comment on a previous post. Can someone help me?

I took my grandmother’s Myheritage test. Her name is Anna Blumer, and she is the granddaughter of Swiss people who came to Brazil (in 1853) from a small isolated city called Matt (and Engi who is located 3 km away) At that time there were approximately 1000 people in these 2 villages. And a distant relative of mine who lives in Switzerland did the test too. Her name is Hedwig Marti. We know that my grandmother is 5th cousin of a parent of Hedwig. All her parents came from this two village as well. However, in the familysearch DNA test it says they are cousin/in-grandchild – 2nd cousin/in-grandchild (they share 1.7% of the DNA). Is this increase due to endomy?

We have the entire family tree from (from the swiss part, from 1600 until today) and in addition to my grandmother being the 5th cousin of a parent of Hedwig, she is also 6th cousin, 7th cousin, a daughter of a 7th cousin, a daughter of a 7th cousin, a a 8th cousin and much much much more. Why is the shared dna 1,7 and not less, let”s say, 0,5%? Ist it because there’re a kind of erdogamy?

Thanks by advance